A

William K. Everson wrote a lot. But he didn't seem to write very much about Thelma Todd.

William K. Everson

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| William K. Everson | |

|---|---|

| Born | William Keith Everson April 8, 1929 Yeovil, Somerset, England |

| Died | April 14, 1996 New York City |

Early life and career

Everson was born in Yeovil, Somerset, England, the son of Catherine (née Ward) and Percival Wilfred Everson, an aircraft engineer.[1] Bill Everson's earliest jobs were in the motion picture industry; as a teenager he was employed at Renown Pictures as publicity manager. He began to write film criticism and operated several film societies.[2]Later career

Following service in the British Army from 1946 to 1948, Everson worked as a cinema theatre manager for London's Monseigneur News Theatres.[2] Emigrating to the United States in 1950 at age 21, he worked in the publicity department of Monogram Pictures (later Allied Artists)[3] and subsequently became a freelance publicist.[2] Concurrently with his employment as writer, editor and researcher on the TV series Movie Museum and Silents Please,[2] Everson became dedicated to preserving films from the silent era to the 1940s which otherwise would have been lost. Through his industry connections, he began to acquire feature films and short subjects that were slated to be destroyed or abandoned.[4] Many of his discoveries were projected at his Manhattan film group, the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, originally founded by Huff (the biographer of Charlie Chaplin), Everson, film critic Seymour Stern and Variety columnist Herman G. Weinberg as the Theodore Huff Film Society. After Huff's death, Everson added the word "Memorial."At each screening, Huff members were presented with extensive program notes written by Everson about each film. During the 1960s, these screenings were held in a hall at Union Square.[2] Occasionally, he would make special arrangements with a select invited group to see a 35mm print in a theater. For example, on a Sunday morning in the mid-1960s, he took over Daniel Talbot's New Yorker Theater to show the silent She (1925) to an audience of no more than 15 silent-film buffs. Later, the Huff Society screenings relocated from Union Square to The New School, by invitation of Everson's friend and fellow Huff Society member Joseph Goldberg, who was a professor at The New School.

Everson was an influential figure to the generation of film historians who came of age from the 1960s to the 1980s, many of whom were regulars at his New School screenings. Other attendees at the Huff Society included such New York personalities as author Susan Sontag and publisher Calvin Beck. Kevin Brownlow described an infamous incident at the Huff Society:

- It was a society that showed the rarest films — often in a double bill with a recognised classic. Everson's programme notes became world-famous (and let us hope that some enterprising publisher will bring them out). In 1959, MGM's Ben-Hur received rave reviews and Everson felt that they were not deserved — so he showed the 1925 version at the Huff. Rival collector Raymond Rohauer, experiencing a little trouble himself over a lawsuit from MGM, told the FBI what Everson was doing, and they confronted him after the performance. They seized the print, and Everson spent the next few days squirreling other hot titles around New York. Lillian Gish had to intervene on his behalf. In the 1970s, the FBI instituted a "witch hunt" among film collectors, but by then Everson was too highly respected to be touched. Archives came to depend on him — he would not only loan rare prints for copying or showing, but he would travel the world presenting the films he loved. I was astounded to meet him at an airport weighed down by three times as many cans of films as any human could be expected to carry. He had the uncanny knack of finding lost films. It would be no exaggeration to say that single-handedly, he transformed the attitude of American film enthusiasts towards early cinema.

He worked as a consultant to producers and studios preparing silent-film projects, and collaborated closely with Robert Youngson, screening and assembling the best in silent comedy for Youngson's feature-length revivals. (Everson even wrote some of Youngson's promotional feature articles for publication.) Everson also assisted in the production of the syndicated TV series The Charlie Chaplin Comedy Theatre (1965) and its offshoot feature film The Funniest Man in the World (1967). He was technical advisor on David L. Wolper's TV specials Hollywood, the Golden Years (1961) and The Legend of Rudolph Valentino (1982).[2]

Everson was a prolific writer, and he contributed articles and reviews to numerous film magazines, including Films in Review, Variety and Castle of Frankenstein. His nearly 20 books include Classics of the Silent Screen (1959, attributed to nostalgia maven Joe Franklin but actually written by Everson), The American Movie (1963), The Films of Laurel and Hardy (1967), The Art of W. C. Fields (1967), A Pictorial History of the Western Film (1971), and American Silent Film (1978).

From 1964 to 1984 he taught film history at The School of Visual Arts,[2] and from 1972 to 1996 was professor of cinema studies at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts.[3] He also taught film history courses at The New School.[3] Everson's courses often had an emphasis on comedy, Westerns and British films. Everson sometimes discussed film history as a guest on Barry Gray's late-night radio talk show in New York. He appeared as an actor in Louis McMahon's serial parody Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates (1966); the four-part film, made by a cast and crew of like-minded movie buffs, concerned heinous traffic in rare silent-screen masterpieces.[5]

Death and legacy

Everson died of prostate cancer at the age of 67 in Manhattan, and he was survived by his wife, Karen Latham Everson,[2] his daughter, Bambi (named for ballerina Bambi Linn), his son, Griffith and his granddaughter, Sarah. His film collection was taken over by his widow and sold to the George Eastman House. His manuscripts, film screening notes and memorabilia were donated to the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, comprising the William K. Everson Collection.[6]A few years after his death, Everson was inducted into the Monster Kid Hall of Fame at The Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards.

References

- Jump up ^ Profile at filmreference.com

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Grimes, William. "William K. Everson, Historian And Film Preservationist, 67." The New York Times, 16 April 1996.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Everson biography at New York University

- Jump up ^ Turner Classic Movies

- Jump up ^ Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates at the Internet Movie Database

- Jump up ^ William K. Everson Collection at New York University

External links

- William K. Everson at the Internet Movie Database

- William K. Everson obituary by Kevin Brownlow, The Independent (bottom of page)

- William K. Everson Archive: New York University, Department of Cinema Studies

- Everson biography at Turner Classic Movies

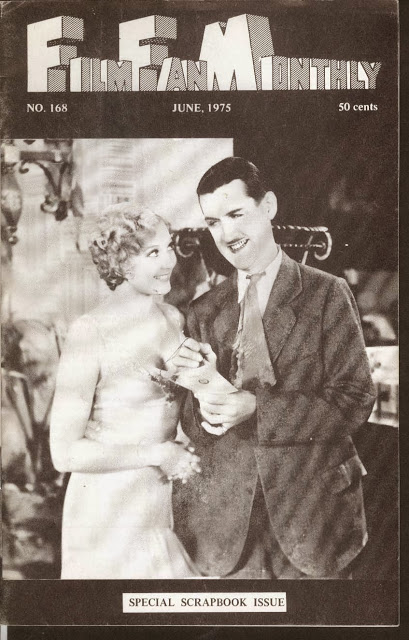

William K. Everson's book THE FILMS OF LAUREL AND HARDY

William K. Everson's book THE FILMS OF LAUREL AND HARDY does not have one word about Thelma Todd in it apart from identifying her in a picture or two and listing her as having been in a film or two along with Laurel and Hardy. He does not have her listed among the casts of all the films she made with Laurel and Hardy. It is the worst book about Laurel and Hardy ever written if you are a fan of Thelma Todd.

Richard W. Bann's comments on Everson's book, having to do with Dorothy Christie:

Reblogged from http://www.laurel-and-hardy.com/films/features/sons-cast.html

The late Bill Everson, author, professor, mentor, revered by everyone who knows and cares about great films of the past, was not always as precise as he might have been keeping facts, or the names of actresses straight. As great as he was, he did suffer from having seen too many films. Really, it was an occupational hazard; he saw too many films. Starting in the 1960s, he caused some confusion by mistakenly listing Dorothy Christy (misspelled "Christie) as Mrs. Hardy in THAT'S MY WIFE (1929), and as Mrs. Laurel in BLOTTO (1930). She did appear in a film based upon a Lucien Littlefield ("Dr. Horace Meddick") original story entitled EARLY TO BED (1936), which was not related in any other way to the same-named Laurel & Hardy film. Also, as mentioned, she appeared in SUNSET ON THE DESERT (1942), and in BIG BUSINESS GIRL (1931). This last was ably directed by her friend, Bill Seiter. He was the one who recommended her for the part in SONS OF THE DESERT.

William K. Everson's history of the Hal Roach studios doesn't have a lot about Thelma Todd, either. Concerning Carole Landis, author Eric Gans remarks in his book CAROLE LANDIS: A MOST BEAUTIFUL GIRL that "she is barely mentioned in William Everson's THE FILMS OF HAL ROACH".

THE DETECTIVE IN FILM:

William K. Everson in The Detective in Film called Roland West “a dilettante director who worked because he liked making films, and one of the peculiarities he indulged was a fondness for shooting only at night. His films were literally dark, nightmarish, shot at night as well as taking place at night.”

I don't know about the part about Roland West making movies because he liked making movies. He could have at one time, but then he quit making movies because he didn't like making movies. That was also the reason he only worked at night. He couldn't stand it when studio bosses interfered with his work.*

In THE DETECTIVE IN FILM, William K. Everson discusses CORSAIR and remarks that the end allows the lawless plotters to escape unpunished with their ill-gotten gains. But Mayo Methot's character does not escape - the story has it that she is killed as a result of having become involved in the plot. Something that is completely ignored by Everson, who could have seen some sort of parallel between this and the death of Thelma Todd ( the two were similar in appearance in CORSAIR ), but missed it in his attempts to relate the happenings in this movie to West's personal views and his possible involvement in the death of Thelma Todd. Thelma Todd is not mentioned at all, apart from the reference to suspicion that West was responsible for her death. As Everson never said anything about Thelma Todd having been in CORSAIR, the implication is that he may not have even known that "Alison Loyd"actually was Thelma Todd.

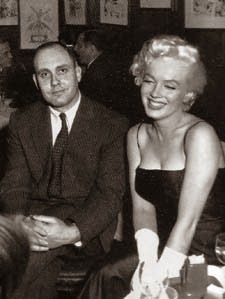

William K. Everson with Marilyn Monroe.

Something that looks better than a picture of just William K. Everson.

THE SERIAL

William K. Everson did make one serial, so he can be said to have made movies as well as writing about them, and even that he can be considered a star of short subjects. Which helps.

*Brad Schreiber thought that some of the problems between Roland West and Thelma Todd were related to Roland West not wanting to work and staying home all the time.

CORSAIR:

http://benny-drinnon.blogspot.com/2012/11/corsair.html

William K. Everson:

http://www.nyu.edu/projects/wke/index.php

A